Understanding private equity

Private equity refers to investing in privately held companies – businesses that are not listed on public stock exchanges. Instead of buying and selling shares on the open market, private equity investors work directly with companies, providing capital to help them grow, restructure, or transition ownership. The goal is to enhance the value of these companies over time, ultimately generating a return when the business is sold, taken public, or recapitalised.

Private equity has become a key engine of business growth and innovation. These investments often help companies expand into new markets, hire talent, and improve operations. In doing so, private equity firms become active partners, not just passive investors.

A large and growing segment of the global investment landscape

Private equity has experienced significant growth over the past two decades, evolving from a niche investment strategy into a core allocation for institutional and, increasingly, individual investors. Since 2000, global private equity assets under management (AUM) have grown more than twentyfold – from under $500 billion to nearly $10.8tn at the close of 2024. [1]

This expansion reflects both strong historical performance and a structural shift in how companies are financed, with more firms staying private for longer and turning to private capital to fuel their growth.

Key drivers of growth

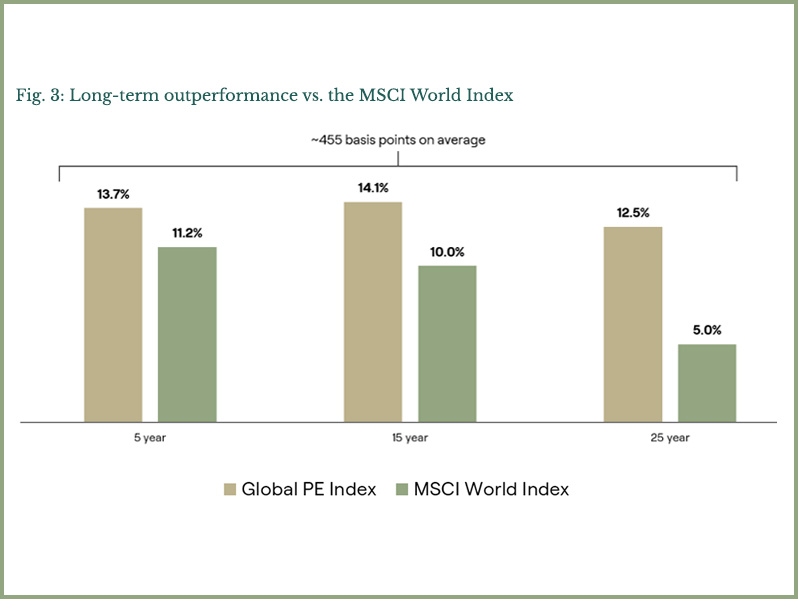

- Return potential: Private equity has consistently outperformed public equities over long time horizons, with top-quartile funds generating net returns in the mid-to-high teens.

- Institutional demand: Pension funds, endowments, and sovereign wealth funds have steadily increased allocations to private equity to meet long-term return targets.

- Private market dominance: The number of publicly listed U.S. companies has declined by over 45% since the late 1990s, while the number of private companies receiving institutional capital has surged, making private equity a critical gateway to accessing corporate growth (source: WDI).

- Individual investor access: Technological and regulatory changes are now enabling high-net-worth individuals and their advisors to participate in private equity strategies once limited to large institutions.

Core investment strategies

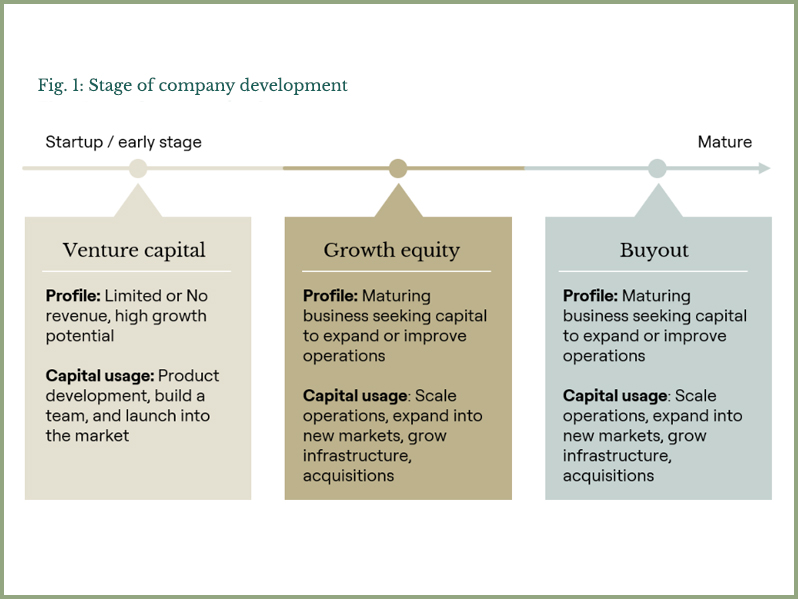

Private equity encompasses a range of investment strategies, each targeting companies at different stages of development. The three primary approaches – Venture capital, Growth equity, and Buyouts – differ in risk profile, investment size, and level of operational involvement. Understanding these strategies helps clarify how private equity managers create value across the business lifecycle.

The investment lifecycle

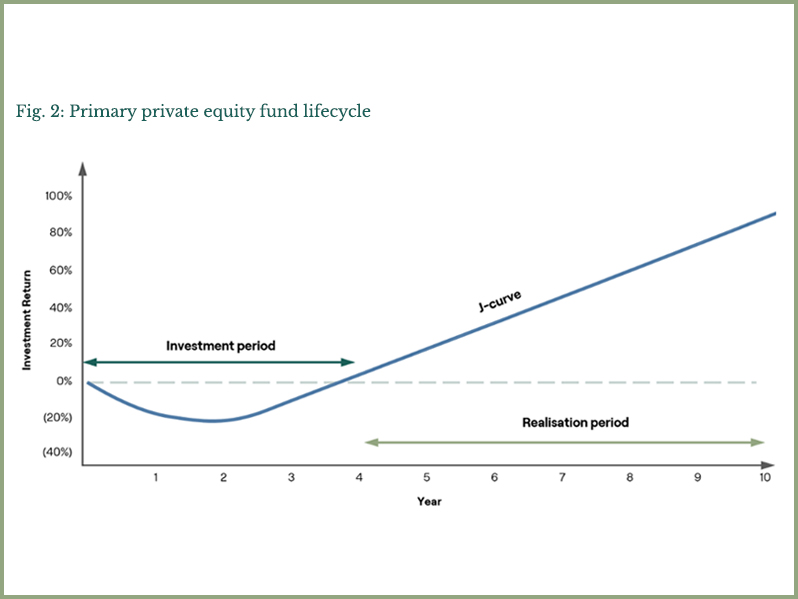

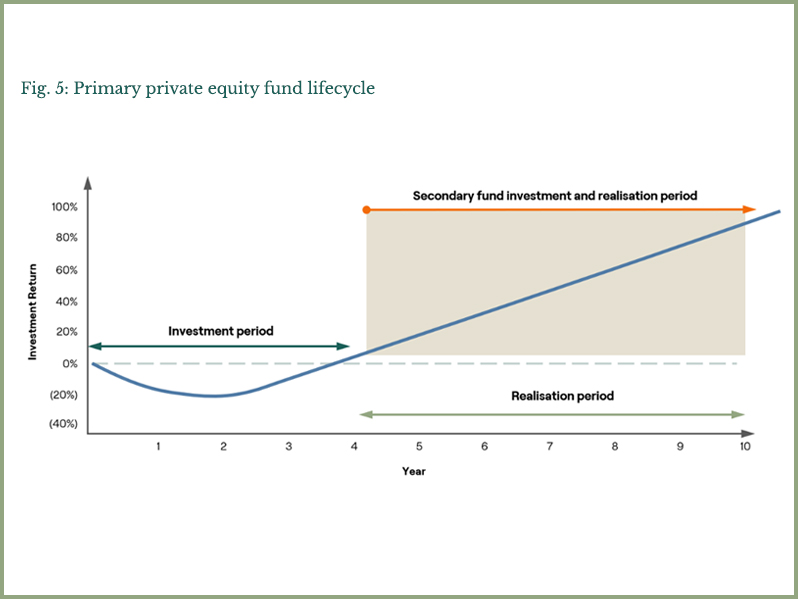

Investing in a private equity fund is a long-term commitment – typically lasting 10+ years. Over this time, your capital follows a lifecycle with two primary phases: the Investment period and the Realisation period. These phases shape how and when your capital is deployed, managed, and ultimately returned.

Investment period (Years 1-4)

In the early years of the fund, the manager actively sources deals and builds a portfolio. This is when your capital is gradually “called” as investments are made. Because fees are charged and investments take time to mature, early returns often appear negative. This is a normal part of private equity investing and is known as the J-curve effect.

What is the J-Curve?

The J-curve describes the typical return pattern of a private equity fund. Early in the fund’s life, returns dip into negative territory as capital is invested and fees are paid, but before any exits or gains are realised. As the fund matures and successful exits occur, returns trend upward – often significantly – forming a curve that resembles the letter “J”.

Realisation period (Years 6-10+)

As the fund moves into its later years, the focus shifts from investing to harvesting value. The manager works to grow portfolio companies and eventually exits them through sales or IPOs. This is when investors begin to receive distributions, and the fund’s performance becomes more visible. The realisation period is where the J-curve begins to turn upward, reflecting the potential long-term value creation of private equity.

Historical performance and portfolio benefits

Private equity has historically delivered strong long-term returns, often outperforming public equities. By investing in privately held businesses, fund managers can unlock value through operational improvements, strategic growth, and active ownership. These investments are typically less correlated with public markets, offering potential diversification benefits. Over time, the combination of value creation and disciplined exits has contributed to the asset class’s attractive performance relative to public benchmarks like the MSCI World Index.

In addition to strong historical returns and diversification, private equity offers investors access to innovative, high-growth companies that are often unavailable in public markets. The long-term investment horizon encourages a patient capital approach, which can help smooth short-term volatility and align with generational wealth planning. When thoughtfully integrated into a portfolio, private equity can enhance overall risk-adjusted returns and provide meaningful exposure to the engines of global economic growth.

The rise of private equity secondaries

Private equity secondaries involve the purchase and sale of existing interests in private equity funds or portfolios of private companies. Rather than committing capital to a new private equity fund (a primary investment), secondary buyers acquire stakes mid-life, often at a discount, providing liquidity to existing investors and more immediate exposure to underlying assets.

The secondary market has grown in both size and sophistication. In 2024 alone, secondary transaction volume reached over $160 billion, with both institutional and private wealth investors increasing allocations.

Understanding secondaries transactions

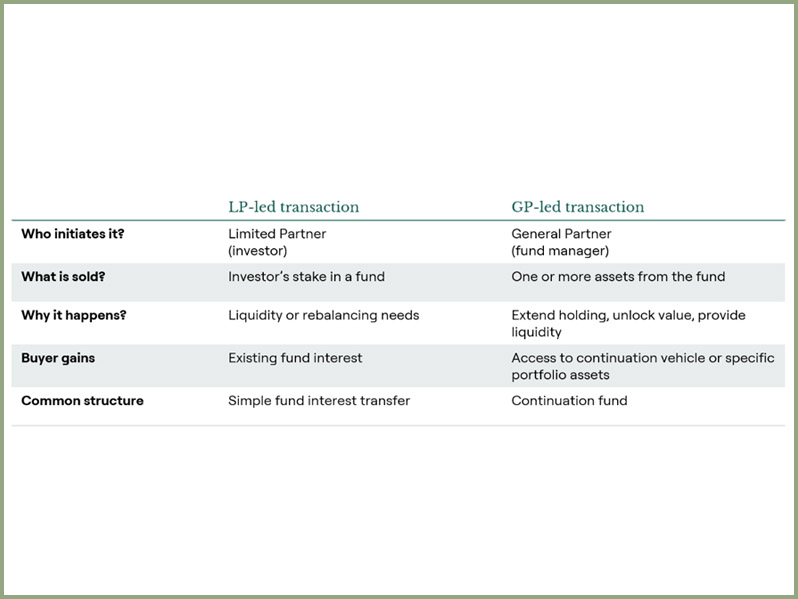

Secondaries investing allows investors to buy interests in private equity funds or portfolios on the secondary market. These transactions typically fall into two categories:

- LP-led transactions: These occur when a limited partner (LP) – like a pension fund, endowment, or individual investor – wants to sell their interest in a private equity fund before the fund’s natural end. The buyer steps in to take over their position, gaining access to an existing portfolio of investments.

Think of it as: An investor exiting early and another stepping in midstream.

- GP-led transactions: These are initiated by the general partner (GP), the manager of the fund, who offers existing investors the option to sell their interests or roll them into a new vehicle known as a continuation fund. This often happens when the GP wants more time or capital to maximize value from a specific company or portfolio.

Think of it as: The fund manager creating a new path forward for select investments.

Secondaries investment lifecycle

Unlike primary private equity funds, which invest in companies over the first several years and follow a long J-Curve timeline, secondaries investors typically acquire interests in funds that are already partway through their lifecycle. This means much of the capital is invested in more mature companies, with clearer visibility into performance and a shorter path to potential distributions. As a result, secondaries can offer reduced J-Curve effects and quicker return profiles.

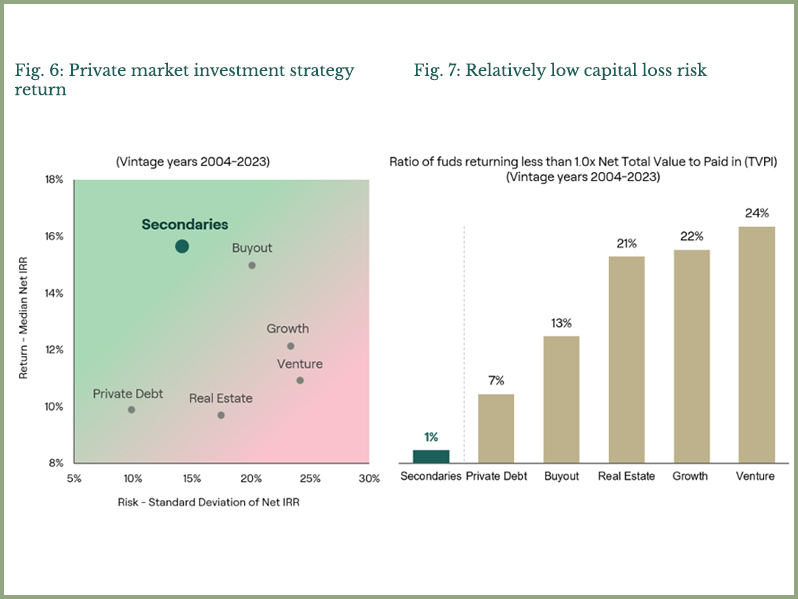

A history of attractive risk-adjusted performance

Private equity secondaries have historically delivered compelling risk-adjusted returns with lower loss rates than many other private market strategies. By offering differentiated access to seasoned portfolios, secondaries can complement primary private equity investments while addressing some of their inherent challenges.

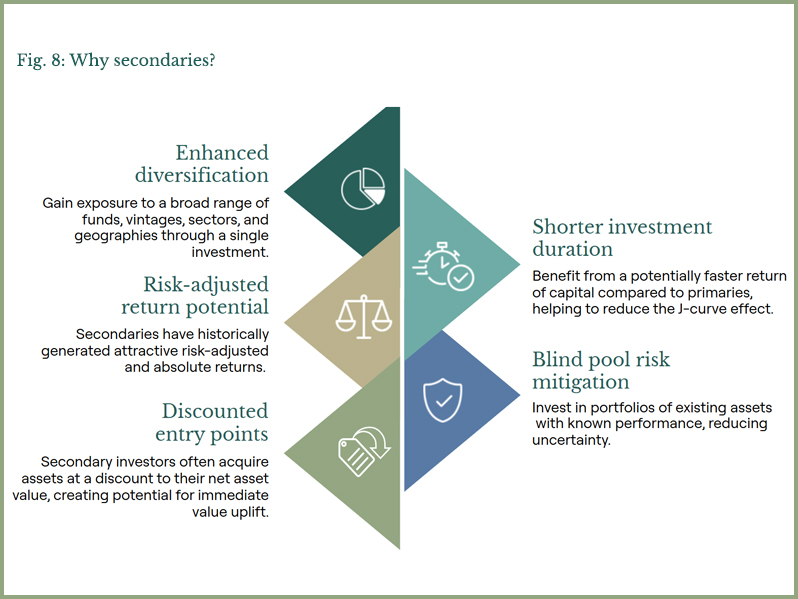

Why secondaries?

A growing role as a core allocation in private portfolios

As private equity continues to grow and evolve, secondaries have emerged as a strategic tool for accessing high-quality assets with improved liquidity and visibility. For financial advisors and individual investors seeking smarter ways to participate in private markets, secondaries offer a compelling mix of diversification, efficiency, and mid-to-long term capital appreciation.